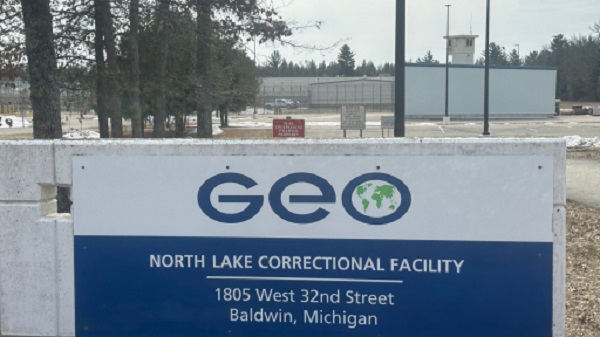

WEBBER TOWNSHIP, Mich. — In the rural expanse of Lake County, Michigan, the closure of the North Lake Correctional Facility in 2022 has left a profound economic void. Once a beacon of employment and tax revenue, the facility’s shuttering has intensified the financial struggles faced by one of Michigan’s poorest counties. The 1,800-bed private prison, owned by Florida-based GEO Group, was a key employer for the area, providing hundreds of jobs and substantial tax contributions. Now, with boarded-up homes and vacant businesses scattered across the county, many wonder if reopening the prison might be the key to revitalizing the local economy.

The facility closed following President Joe Biden’s executive order to phase out the federal government’s use of private prisons. While the move was lauded by some as a step toward criminal justice reform, its effects on local communities like Lake County have been severe. The prison, which once employed up to 300 people, was the largest taxpayer in the region, helping to fund vital services in a county with a poverty rate of 21%, well above the state average.

But now, as national politics shift, the GEO Group is exploring the possibility of reopening the prison—this time, to house detainees for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). According to documents obtained by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) through the Freedom of Information Act, the GEO Group has offered to repurpose the facility for immigration detention purposes, as ICE seeks to expand its capacity to hold individuals arrested during immigration enforcement operations.

While the GEO Group declined to comment on the matter, an ICE spokesperson confirmed that the agency is “exploring all options” to meet its current and future detention needs. The potential reopening of the facility has sparked both hope and concern within the community.

Local government officials, including Lake County Administrator Tobi Lake, emphasize the economic importance of the prison. “At the end of the day, besides what your philosophical view is or your morality, they are the biggest taxpayer, and when they’re open, they’re the biggest employer in our county,” said Lake. The administrator pointed out that the prison’s closure has not only deprived the county of jobs but also diminished its tax revenue, which funds everything from public safety to local schools.

However, critics, including ACLU attorney Eunice Cho, argue that reopening the prison as an immigration detention facility would do more harm than good. Cho raised concerns about the ethical implications of using public resources for private detention facilities, noting that such moves would likely divert funding away from crucial services like education and veterans’ support. “This is money that could go to important programs for our communities, not into the pockets of private prison companies,” Cho said.

The ACLU also warned that immigration detention centers often lead to heightened enforcement actions in surrounding areas. “Any time an immigration detention facility opens in a community, it certainly increases the risk that people in the local community could be more vulnerable to immigration enforcement and detention,” Cho said.

Yet, not all in Lake County are opposed to the idea. Some residents, particularly those struggling with the county’s high poverty rate, view the reopening of the prison as a necessary economic lifeline. John Arndt, a local resident who lives in a camper near the prison, expressed support for the potential reopening. “I’m not opposed to that at all,” Arndt said. “It’s a facility that would employ people here.”

Larry Reed, president of the Lake County Chamber of Commerce, echoed similar sentiments. He pointed to the severe economic challenges facing the community, where businesses and residents are grappling with the aftereffects of the prison’s closure. “Lake County is one of the poorest counties in the state,” Reed said. “We would just like to see the facility opened again, in any capacity.”

The prospect of reopening the prison is not without controversy. While some view it as a necessary step to restore jobs and revenue to the community, others fear the social and ethical implications of housing immigration detainees in a county already struggling with deep poverty.

Meanwhile, GEO Group has asked the Michigan Tax Tribunal to reduce the prison’s taxable value from $27.5 million to $15 million, a move that could significantly affect local tax revenue. If granted, the reduction could cost local and state governments, along with the local school district, an estimated $600,000 in revenue—further straining an already fragile financial situation.

As Lake County continues to weigh its options, the decision about the prison’s future remains uncertain. For many, the debate centers not only on economic necessity but on the broader question of how the community should balance financial survival with ethical considerations surrounding private detention facilities.

The outcome of this debate could set the tone for how Lake County, and communities like it, navigate the complex intersection of federal policy, economic need, and social justice in the years to come.